|

Victorian & Edwardian Services (Houses) 1850-1914 |

|

|

|

2 1850s - Middle Class

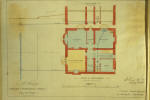

| Any large, well-appointed middle class home required a reliable water supply

and in the mid-nineteenth century this was a major preoccupation for the

builder. The supply of mains water by private or municipally owned water

companies was then still in its infancy and few houses were connected to piped

water. Each house, therefore, had to be self-sufficient in this respect. One

source was spring water. Establishing its presence was an important preliminary

to construction work and could even determine the precise location of a house

and so sinking a well was the usually the first building operation undertaken

before the foundations were laid. The circular shafts with a minimum diameter of

three feet were lined with brickwork and most were no deeper than thirty feet,

the maximum depth at which a common iron suction pump could function. Where

possible the well was dug close to the proposed site of the scullery or kitchen.

Spring water was – in theory, at least - relatively pure and safe to drink but

it was usually hard and not suited to laundering purposes as it caused soap to

curdle. For doing the weekly wash and for other scullery uses rainwater was

used. An average sized roof yielded between 21,000 and 35,000 gallons of water

per year and so many good quality houses were supplied with large rainwater

storage tanks in the basement from which the water was again drawn by a hand

pump. |

|

Good quality houses available for letting were often advertised as having

‘both kinds of water’ but water remained a scarce and unreliable commodity until

after about the 1870s. Spring water from relatively shallow wells was liable to

contamination from leaking or overflowing cesspools and this was often the cause

of local outbreaks of typhoid and cholera. The scarcity of water also

circumscribed how people kept themselves clean. Bathrooms were rare before the

1870s and most middle class families used small portable baths of tinplate which

had to be filled and emptied by hand using servant labour. On a daily basis many

people washed themselves using a ewer and basin of water set on a wash stand in

the bedroom.

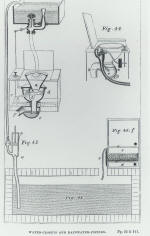

By 1850, virtually all middle class homes were equipped with a water closet. These were generally of two kinds: the valve closet and the pan closet. Both

relied on a system of levers and cranks to operate a valve or pan to discharge

the waste. The closet bowl and the mechanics were enclosed under a fixed

mahogany seat and the flush water supplied from an overhead cistern which was

typically filled by hand pumping water up from the basement rain water reserve.

Pan closets were cheaper than valve closets and of a more robust construction

but from the 1870s they were exposed as being unsanitary due to the

impossibility of flushing clean their cavernous interiors. Both valve and pan

closets were usually sealed from the soil pipe by the highly inefficient

D-shaped water sealed traps which were not self-cleansing and often, therefore,

the source of foul smells whenever the device was flushed. Sewage disposal was

notoriously inadequate or even non existent at this time with WCs variously

discharging liquid sewage directly into storm drains and ultimately into rivers

or even into street gutters. Most decanted the sewage into cesspools dug in the

back yards or gardens of the property and periodically these had to be emptied

by nightmen who generally carried out this noisome task during the hours of

darkness. |

|

The family would usually take their baths in the privacy

of their bedroom or in an adjacent dressing room but the water usually

had to be carried up from the

basement service area which would comprise a kitchen, scullery, pantry and

larder and also stores for coal and ash. The service areas of the largest villas

would also include a housekeeper’s room and butler’s office. Most service areas

also contained a WC purely for servant use and in place of the expensive

mechanical closets used by the family upstairs, they usually took the form of a

simple ceramic basin attached to a water sealed trap. There were several

variations of basin and trap closets according to the shape of the basin: thus

there were long and short straight sided hopper closets whilst those with a

rounded profile were known in the trade as ‘cottage’ or ‘servants’ closets’. |

|

The kitchen contained a large fireplace – typically five feet wide - whilst a

large dresser was usually fixed on the opposite wall. In most substantial houses

the water supply and the sink was located in the scullery along with a wash

copper set in brick and containing its own small firebox. The sink was usually

made of a hard sandstone or grit such as York stone and placed on a brick plinth

below a window. The kitchen fireplace opening was usually occupied by a large

cast-iron range consisting of a coal burning grate flanked by an oven and

boiler. The range was either open to the chimney or enclosed on top by a hot

plate which forced the hot draught to circulate around the oven and boiler

before being lost to the chimney. These closed ranges were held to be cleaner

and more efficient but in reality they consumed prodigious quantities of coal

and were, besides, time consuming to maintain. |

|

|

Coal fires were also the chief means of room heating. In the 1850s and 1860s,

the principal rooms of a middle class villa were supplied with the fashionable

‘arch plate register grate’. The grate – as the name suggests – was framed by an

ornate round arched opening. Immediately above the grate there was a small

D-shaped hatch known as a register door which provided rudimentary control over

the air supply to the fire and when closed sealed off the fireplace completely

from the chimney flue. Small hob grates, which had the front fire-bars set

between two cast-iron panels, were fitted in the fireplaces of the rooms on the

upper floors. |

|

The light of a coal fire was also a valuable source of artificial light

although by the 1850s many middle class homes had gas laid on for lighting.

Amongst the well to do, gas was regarded as excessively harsh and bright and,

moreover, associated with use in industrial and public spaces: the soft light of

oil lamps and candles was widely preferred. Nevertheless, the principal

reception rooms were usually fitted with gas chandeliers – or gasoliers –

suspended from a central ceiling rose. They were always fitted with a ball and

socket joint to enable them to be moved to one side and with a water slide which

enabled vertical adjustment. Gasoliers were made up of several simple flat flame

burners usually of the ‘union-jet’ or ‘fish-tail’ pattern which were made of

cast-iron or brass with the top of the burner consisting of some non-conducting

material such as steatite, a natural stone which, after firing was practically

indestructible. Two orifices were drilled at an angle in the top so that two

streams of gas impinged on each other to spread the flame to something like the

tail of a fish. They were poor light givers but lent themselves to gasoliers and

lamps with globes of glass as they did not produce a ragged flame. The use of

gas lighting on the upper floors was often restricted at this period to the

landing and the average middle class family probably retired to bed by the light

of a candle. |

| Downstairs in the service area, flat flame gas burners without glass shades

were generally used. The kitchen was sometimes illuminated by a pendant light

with two burners suspended over the main work table although bracket gas burners

fixed to a round wooden block known as a ‘pattress’ were also widely used and

fixed above the mantle shelf above the range. These had either fish-tail burners

or the bats-wing burner made with a slit in a domed top. The bats-wing burner

produced a good light but the flame was inclined to be ragged with ‘horny’ ends

and so was not suited for use with a globe. |

|

|