Traditional Timber Framing - A Brief Introduction

3 From Trees to Timber

The predominant timber species used for structural purposes in England and Wales was oak. This is an immensely strong, durable and long grained timber. Elm, sweet chestnut, hornbeam and other timbers were also used. Typically timbers were used unseasoned, shortly after felling. ‘Green’ Oak and other timbers were considerably easier to work and joint than seasoned timber and given the typical cross sections air seasoning would have been impractical.

Foresters and carpenters had an intrinsic understanding of the nature of trees and timber they used. The most prized part of the trunk was the inner section of timber known as the heartwood. This contains the densest and most durable timber. The outer section of the trunks, the bark and sapwood have the dual purpose of protecting the heartwood and more importantly distributing food and water necessary for growth. The sapwood is the point at which an additional growth layer occurs each year, it is far less dense than the heartwood and it also contains a much higher level of sugars and moisture, making it far more susceptible to insect attack and fungal decay.

Medieval carpenters selected the smallest tree necessary for the job. There were three methods for the conversion of logs to useable timber; sawing, hewing and riving. Sawing was undertaken with a two handled saw with the trunk laid on trestles (see sawing and vertical sawing) or over a pit. The straight lines for marking out the saw cuts on the irregular logs were made using a chalked string line stretched taut, providing a relatively straight and plane surface. Hewing uses a variety of specialist axes including adzes to produce a straight, plane and frequently squared surface on irregular logs. In common with the marking of logs for sawing, chalklines provided the guide lines for true surfaces. A high proportion of the timbers in medieval buildings were riven. That is they were split along the grain. This was a much less reliable method of producing timbers of a predetermined size as the logs would split along the grain at the point of natural weakness. Riving produced timbers which were relatively strong. Unlike sawn timber the full length of the grain was intact and had not been cut through as would be the case if it had been sawn.

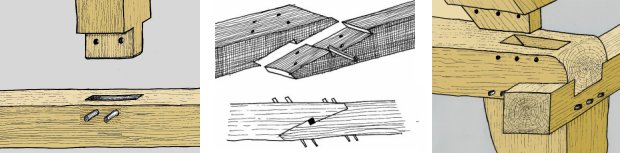

The Joinery

Carpenters developed complex new joints and assemblies for dealing with new structural problems although some of the pre 1200 joints continued to be used. The mortice and tenon (known to have been used for thousands of years - and shown on the left in the graphic below) gradually replaced the simpler and even more ancient lap joint as the most common joint throughout timber framing. In common with most timber framing joints, mortice and tenons were secured by timber pegs when the final erection of the building occurred. Using a system known as draw boring the hole for the peg in the sides of the mortice was slightly off-set on the tenon so that when the peg was finally driven through, the whole joint tightened up. Pegs provide considerable resistance to withdrawal but over stressing could, and did, cause failure. Improvements in their understanding of geometry enabled carpenters to develop complex lengthening joints known as scarf joints (middle below). Using these joints the carpenters were able to provide timbers longer than those which were naturally available. The right hand graphic shows the complex joint where a post meets the wall plate, tie beam and roof structure.

except where acknowledged