Evolution of Building Elements

6 Windows

Early windows were usually fixed lights or side-hung casements. All the examples below are mid to late 17th century. The timber window on the far left is part of a timber framed house built in Bristolís dock area. The second example shows a stone building (c1690) with timber window frames glazed with diamond shaped leaded glass (small panes of glass were much cheaper than large sheets). A hinged, wrought iron casement has been fitted into the right hand section of window. The window on the right has a fixed light directly glazed into the stonework and a hinged iron casement.

In the late 17th century sash windows were introduced to Britain. These windows were usually still formed in small panes because of the limitations of glass technology. The timber sections were quite thick and the window was set flush with the face of the brick or stonework (left hand photo - about 1710). The windows were controlled with lead (later iron) weights which counter-balanced the weight of the sashes. During the Georgian period the glazing bars became thinner and thinner and, at the same time, the windows were set in rebates which hid the box frames. In houses with thick walls the inner reveals often contained shutters (centre photo - about 1800). From the late 18th century onwards it became fashionable (for the wealthy at least) to have full length windows on the first floor leading onto a wrought and cast iron balcony.

Windows are visually important architectural elements. For example windows were integral to the architectural philosophy of the Georgian era, where their proportions were closely defined in relation to the dictates of symmetry. During the Georgian era window tax was introduced. This was levied on the number of windows in a house and goes some way towards explaining why some windows from this era were blocked up. In the middle of the 19th century this tax was dropped. This change was accompanied by increasing concern with daylight and ventilation, which the Victorians associated with good health. Consequently there was a move towards stipulating minimum window sizes. Towards the end of the Victorian period improvements in glass technology precluded the need for glazing bars altogether.

In the 1920s top hung and side hung casements became popular. The example on the left is from about 1920 and is a crude example of Queen Anne revival sash windows; they were popular during the Edwardian period and were characterised by having a small-paned top sash over a single paned bottom sash - white paint was de rigeur. The right-hand example is from the mid 1930s; casement windows with top hung leaded top-lights (often glazed with stained glass).

Metal windows, introduced in the very late 19th century, were very common until the 1970s. Early windows were plain mild steel; from the 1930s they were mostly galvanised. As houses became better insulated and less well ventilated their shortcomings became more obvious - the cold inner face of the frames resulted in condensation.

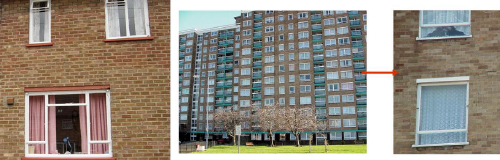

In the post war period high rise housing required new approaches to window styles. Traditional sash windows could not possibly withstand the turbulence and exposure at high levels, and casement windows would be impossible to clean. A common form of window was the horizontal pivot window. These could be made from galvanised metal, timber or aluminium and could be cleaned from the inside.

Aluminium windows (below left) became very popular during the 1970s but, in recent years, have almost completely been eclipsed by plastic. Aluminium windows, like galvanised metal, are good conductors of heat and condensation is always likely to be a problem. In the 1970s a policy of rehabilitating older properties replaced slum clearance and high rise construction. In many cases budgets were not adequate and houses, originally refurbished for 30 years or so, required substantial extra investment after less than 10 years. One example of cost cutting was the louvre window (below right). These were cheap to make, just requiring a simple softwood frame, but were draughty, provided inadequate ventilation in the Summer, and could not readily be used as a means of escape. Other rehab and new houses were fitted with 'standard' timber windows. There were hundreds of styles (below middle). These windows were cheap but mostly made from poor quality timber.

Nowadays, windows are usually made from imported softwoods and hardwoods, or from plastic. There are literally hundreds of styles to choose from. The public has become accustomed to renewing windows, almost as fashion accessories, and often well in advance of their likely life. Because of this, replacement windows has become a very big, but in some cases completely unnecessary, business. The design of windows and the choice of material used may be controlled by planning authorities in conservation areas. Plastic replacement windows are a focus for concern in such areas because they affect character and appearance. Even outside conservation areas the replacement of wooden sash windows will have a significant visual affect on say a street of Victorian terraced houses (below right). The windows on the far right are mock Georgian; the glazing bars are sandwiched between the double glazing.

except where acknowledged