Evolution of Building Elements

4 Upper Floors

Introduction

The upper floor of a modern house is not that much different from its 1800 counterpart. In other words it comprises a series of timber joists (there are modern alternatives) covered with some form of floor boarding. Nowadays we always expect to find a ceiling although, 150 years ago, the joist soffit was often left open in working-class housing. In modern construction the size and spacing of the joists are subject to the Building Regulations. Before 1965 they were mostly controlled by Model Bye-Laws or accepted building practice.

Note that this brief introduction does not include the construction of floors between flats. Information on this can be found under the Floors section of this web site.

Late 19th century

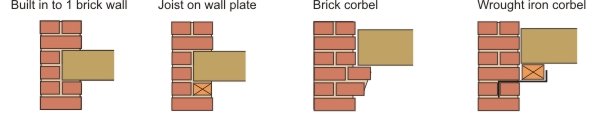

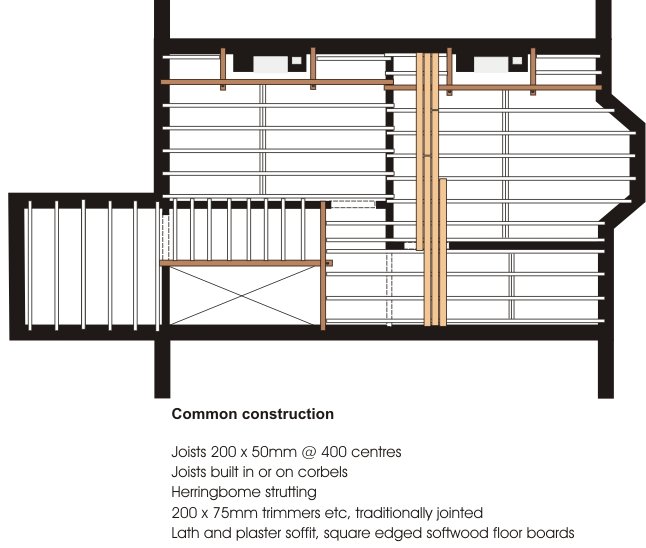

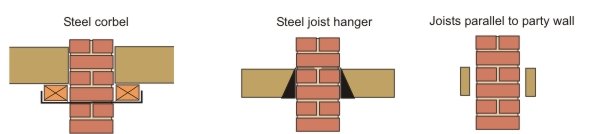

At the end of the 19th century a typical well-built terraced house would have an upper floor constructed from 8" by 2" (200 x 50mm) softwood floor joists fixed at 12" to 16" centres (300 to 400)mm. The joists were usually built in to the walls although occasionally wrought iron or brick corbels were used. Corbels were expensive but did ensure that joists on party walls did not penetrate the brickwork (better sound and fire protection) and that joists on external walls were protected by the full thickness of the wall (less chance of rot).

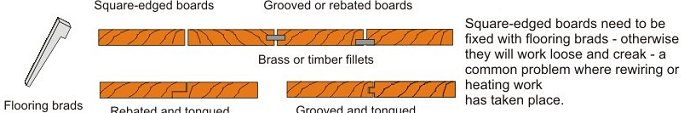

The floor was normally covered with square-edged softwood boards and finished with a lath and plaster ceiling - usually 3 coats of lime plaster. The direction of the joists can either be party wall to party wall, or front to back. The joists were trimmed around fireplaces and stair openings as shown in the graphic. A half-barrel vault supported the hearth. Note that more information on fireplace construction can be found in the Heating section of this web site.

Larger properties may have had double floors, in other words a floor with a primary timber (or steel) beam running at right angles to the joists and supporting them mid span. An advantage of a double floor is that it keeps the floor depth to a minimum and provides all four walls with lateral restraint. Larger, more prestigious, properties sometimes had various types of tongued and grooved boards rather than square edged ones. These are shown further down the page.

1930s

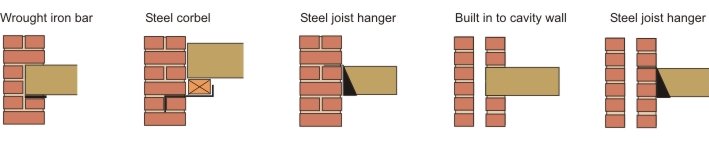

In the 1930s the construction was much the same. Contemporary text books show a number of alternative methods of supporting the joists to suit a Model Bye-law of the time which required that no timber could be built within a half brick of the centre of a party wall. The bye-law also specified that all joists should rest upon a wall plate or steel bearing bar (to spread the load across the wall). In practice these bye-laws were often not adopted by local authorities or just ignored. Text books also suggested that joist ends should be tarred or creosoted where they were built into walls.

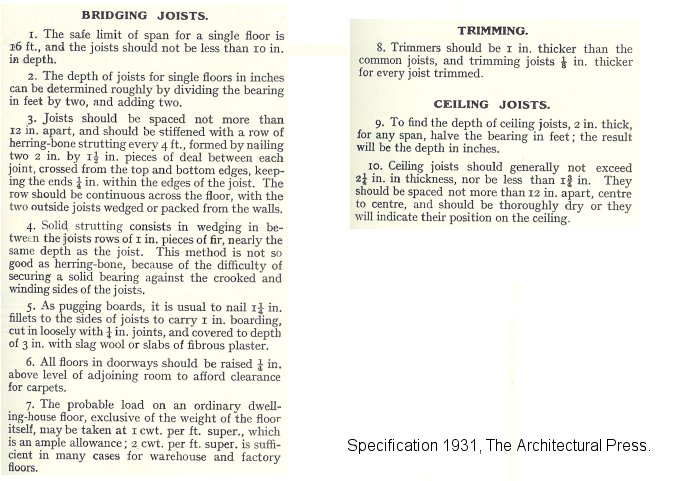

'Specification' from 1931 provides some general guidance on the construction of upper floors (interestingly enough it does not mention the bye-law requirements). Single floors were normally thought to be acceptable for floor spans up to 16 feet; above that double floors were recommended.

Herringbone strutting was normally recommend at 6 feet intervals (1.8 metres). Unlike Victorian and Edwardian floors the hearth support was often in the form of insitu concrete reinforced with mesh rather than a half barrel vault.

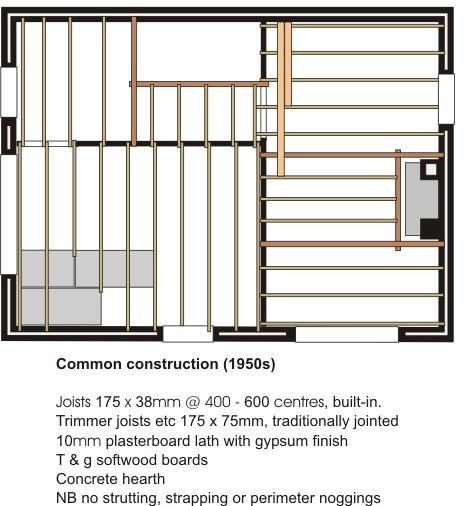

1950s and 1960s

In the post War period timber imports were strictly controlled. Although some system-built houses had floors made from steel joists most houses had fairly traditional upper floors, often with centres 'stretched' and joist sizes reduced, to save timber. In addition strutting was often omitted. Floor coverings were usually tongued and grooved softwood. Boarded ceilings replaced lath and plaster - fibre board, asbestos board and plasterboard (often small sheets - i.e. plasterboard lath) were all common. Joists were built-in or supported on hangers.

By the 1960s timber rationing was over and floor timbers reverted to pre-War sizes. The 1965 Building Regulations introduced tables for sizing floor joists and these remain much the same to this day. During the 1960s plasterboard became virtually the only material used for ceilings. The boarding was normally 10mm or 12.5mm thick (3/8inch or 1/2inch) with an artex or gypsum plaster finish.

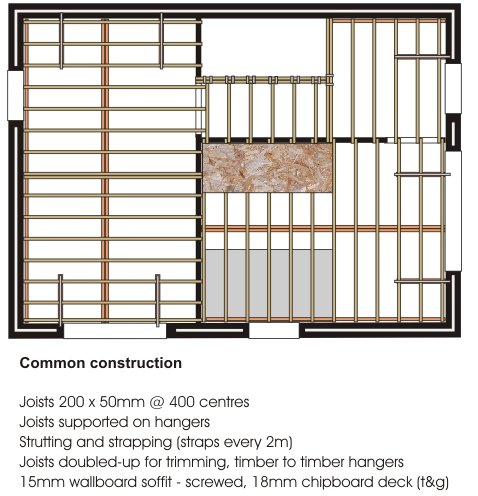

Modern floors

The construction of modern upper floors is shown below. They differ from 1950s floors in three main ways: strapping is now required to restrain the external walls, joist hangers are almost obligatory (to prevent air leakage), and floor boards have largely been replaced by chipboard or strand board. Modern ceilings are still nearly always formed in plasterboard. Nowadays plasterboard lath is rare; the construction usually consists of large sheets of 15mm plasterboard, screwed to joists or to resilient bars, and then taped and painted.

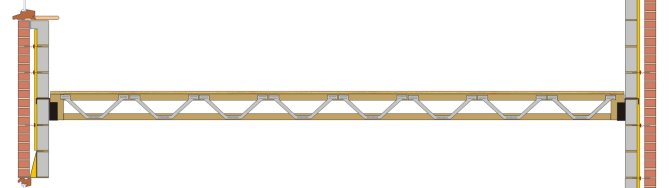

In recent years the use of metal web joists and ‘I’ joists has become more common. In principle these are no different from traditional ‘cut’ joists. One advantage is that they are capable of increased spans. The use of metal web joists also precludes the need for potentially damaging joist notching.

Flats

In flats the floors separate dwellings and, therefore, must provide good fire protection and resistance to the passage of impact and airborne sound. The methods of construction shown above are not suitable. Modern options and a brief historical overview can be found in the Floors section of this web site.

except where acknowledged